The Iberian peninsula

History

In the Renaissance, the events of two years had formative influence on the history of Spain. In 1467, the marriage of Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon secured the union of their two kingdoms. In 1492, at the end of the Reconquista, the fall of Granada terminated a centuries-long Moorish rule on the Iberian Peninsula. In the same year, the remarkable journey of Christopher Columbus took place, financed by Isabella and culminating in the discovery of the New World. In the following decades, Spain became a great power under Charles V (Carlos I 1516-1556) and Philip II (1556-1598). After the annexation of Portugal in 1580, Spain ruled throughout the Iberian Peninsula. The era of the Golden Age was overshadowed by the Spanish Inquisition and the expulsion of the Jews and Moors. Although the devastating defeat of the Spanish naval force (Armada) against England in 1588 seemed to mark the end of this great period, the Spanish fleet has been expanded further with all the more energy. Therefore, it would certainly have been conceivable that Spain could have consolidated its supremacy if insurgent Dutch and Zeelanders had not almost completely destroyed the Armada in Cádiz in a surprise attack in 1607. As a result, Spain had to conclude a ceasefire with the Netherlands.

On the fringes of the 30-year war raging in Germany, military clashes between Spain and France began. The French had supported an uprising in Catalonia, the Spaniards in turn supported the so-called Fronde against Cardinal Mazarin in 1648 in the hope of weakening the French monarchy. However, with the Peace of the Pyrenees of 1659, Spain had to cede parts of Hainaut, Flanders, Artois and Luxembourg to France. In 1640, after an aristocratic revolt under Duke Bragança, Portugal became independent again. After these losses of territory and influence, Spain left the circle of the great European powers, followed by an era of relative insignificance. Nevertheless, Spain continued to trade and expand overseas. The exploitation of the local mineral resources, the import of spices and new crops could continue to guarantee a certain prosperity. However, the demarcation of the border with France in the Pyrenees led to extensive isolation by land.

After the death of the last Spanish Habsburg, King Carlos II in 1700, the War of the Spanish Succession between an Austro-English alliance and France broke out, ending in 1714, with Philip V, the first Bourbon king ascending to the Spanish throne. The Spanish Netherlands had to be ceded to Austria. Philip formed his own state from Castile and Aragon and abolished numerous regional privileges. As the Bourbon monarchy took over the French style centralism to Spain and modernized administration and household, the country began to recover from the consequences of the wars. Towards the end of the 18th century, foreign trade grew again strongly.

Effects on the music

The music reflects the development of the history of Spain in an almost dramatic way. With the political supremacy, the musical culture of Spain also became European. The brilliant organist Antonio de Cabezón traveled numerous European countries, among them Germany, the Netherlands and England, he came into contact with the most important composers of his time (such as Orlando di Lasso or Philipp de Monte) and transferred their works to the keyboard instrument with virtuosity. He was succeeded by Sebastián Aguilera de Heredia and Pablo Bruna at the beginning of the 17th century, marking a certain level, which, despite its appealing quality, remained behind the current development of composing in Europe at the time. A musician like Correa de Arauxo must be regarded as a singular special talent. However, his extremely difficult and impressive compositions have hardly left any traces in music history. In church music a concentration on Spanish traditions can be observed, which hardly allowed innovative elements. However, with Juan Cabanilles, who had good connections to the south of France, an organist from Spain once again achieved a high international reputation.

With the flourishing economy, the churches were able to expand in the second half of the 18th century, so new and sometimes very large organs were acquired. The huge instruments in Granada, Malaga or Toledo bear witness to this prosperity. As in Southern Germany this exorbitant magnanimity in organ building, however, finds no equal in the musical creations of contemporary musicians. Obviously, money did not play any role for those responsible.

Regional organ types

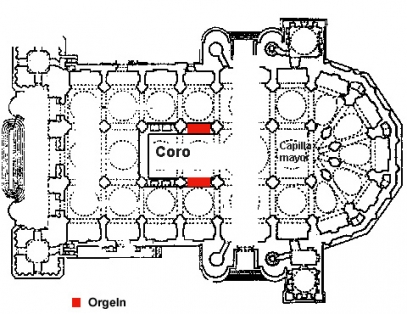

Like in England, Spanish cathedrals maintained the peculiarity of the Coro (see above the typical floor plan of a Spanish cathedral). This is a distinct room behind the crossing with the choir stalls surrounded by choir barriers. The altar room, the Capilla mayor, is separate from the Coro. Depending on the architecture, there are often two pipe fronts, one to the Coro and one to the side aisle. If the side aisles are lower than the main aisle, the façades had to be of different heights.

In abbey churches there is a Coro alto, a choir above the west entrance, where the organs are placed to the two side walls, so no back façades are needed. In Portugal the cathedral chapter joins in the Coro alto or in the Capilla mayor, therefore the organs stand there as choir organs on small galleries on the lateral choir walls.

Already in the 15th century there were two-manual organs in Spain. Around 1800, the size of the instruments grew up to five manual divisions. In the same period also some parapet positives were built, but no chest positives. Instead there is often an elaborate substructure under the manuals, with a simple rocker mechanism but extended wind chests (up to 7 meters in length). Even with up to five different divisions, no more than 3 manuals were built, the additional positives steered by conducts that go from one wind chest to the other. Individually, the separate wind chests can only be operated with check valves.

The common divisions to be found in Spanish organs can be referred to as the main organ, the parapet positive, a base positive and the rearward positive. Occasionally there is also a second parapet positive in the rear facade, for example Sevilla 1724, Málaga 1782. In the 18th century, base positives were redesigned with doors to become an echo, changing soon to swells in Spain (as in England), while separate upper positives only existed in the 16th century. Instead, there are sub-assemblies in the upper case which are connected to the main wind chest by conducts. Presumably because of the problem of an unreliable playing style, long tracker actions were avoided. Thus, the technical system remained simple and low-maintenance throughout, and efforts were made to keep the wind shutters narrow (about key space). Long valves provided sufficient wind supply, the large pipes, which could no longer be accommodated in the small space of the wind chest itself, were discharged. This was done either with conducts which were cut into the (widened) pipe block or with separate conduct tubes. The arrangement of the pipes on the wind chest of the older organs does not correspond to the structure shown in the façade. Usually the arrangement of the pipes is simply chromatic; the pipe position on the wind chest only agrees with the façade after 1700, which also caused the construction of complicated roller boards.

The register cornet is, like in France, raised separately with tubes, sometimes in two floors on top of each other. The superimposition of sections enabled a very flat construction of the cases (low depth). Occasionally, a rear section received its own façade to the side aisle. The installation of two organs on opposite galleries in the Coro recalls the kind of multiple choirs that emerged in the 16th century.

Before 1700, there were organs in Spain with an extended

pedal, up to 21 notes, but the usual compass was only

one octave. The type of music for the organ can be seen as the cause of

the low pedal compasses. Since the composers in Spain and Portugal did not

use independent melodies for the pedal, the organ builders were able

to limit themselves to a minimum of equipment that was sufficient to bring in just some pedal reinforcement in the final passages. As early as 1549 a

reviewer from Murcia had written about the Imperial Organ of Toledo:

'In the pedal there are 13 tones, and you only need 7 whole tones, because the 8th, the c°, is the repetition of the deep C, and with 7 tones in the pedal you can play all music, that exists and will ever exist in the world.'

Another - and probably the most characteristic - feature of Spanish organs is the "Lengueteria" (horizontal reed stops) which stand out horizontally from the front of the façade. This construction seems to have spread like a fashion everywhere in Spain since about 1700. The reason for this could have been the lack of space in the instruments resulting from the structural concept, which hardly allowed expansions. Thus, they took advantage of the technical possibilities and drilled the wind chests from below, added loops and inserted the registers with conducts into the front. In Jaca one can see decorative putti heads in the façade blowing individual trumpet pipes, hence the term Trompeta de los ángeles. Usually a second horizontal register was built soon (Portugal remained at this level), while some spanish organs even possess up to eight such ranks (for example, the Gospel organ in Toledo).

In the one-manual organs, different registers can be drawn for the treble and the bass, divided between the keys c1 and c#1; treble ranks are often lower than their bass counterparts allowing to play lower notes with the right hand, higher with the left, without crossing the division. With this sort of division of the ranks, specific solo registrations were made possible, usually indicated by the term "Medio registro". Then, on paper, the left hand will not ascend beyond c1 while the right hand part uses the lower limit c#1.

The console is always built into the organ case. The stops are divided into bass (left) and treble (right) next to the keyboard. Spanish organs know tremulants and stop valves as play aids and additional registers like bird voices and chimes of all kinds that are common throughout Europe. Pedal couplers were not built, manual couplers are rare.

© Greifenberger Institut für Musikinstrumentenkunde | info@greifenberger-institut.de