Pipe material

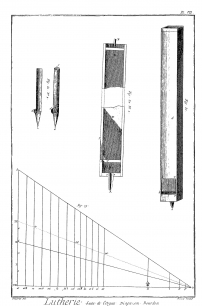

Two material groups are decisive for the construction of organ pipes: metal and wood. Metal pipes are formed from cast metal sheets, which the organ builders usually produced themselves; the pipes then get a round cross-section. Wooden pipes, on the other hand, usually have a square (square or rectangular) cross-section, as they are assembled from individual boards. Only very small wooden pipes were turned occasionally according to the style of the woodwind instrument makers but this always remained an exception and proof of a special effort. Such small wooden pipes also have a reputation of being slightly out of tune, so metal is usually preferred. Very large organ pipes, on the other hand, are usually made of wood, as these pipes require wall thicknesses that can hardly be made of metal.

The wood selected for pipes - oak, beech, maple, occasionally fruit wood, among the softwoods fir, spruce or pine - is primarily intended to be resistant to wood worm infestation and not very sensitive to temperature and humidity fluctuations. Being free of resin and ingrown branches was also important. The size of the pipes also matters, for the deep pipes of a pedal register it is advisable to resort to softer types of wood rather than to oak, which is very expensive in such dimensions and also difficult to process. In the sound of the pipes, differences between the individual types of wood are hardly audible. The choice of the more expensive and harder hardwoods therefore happens less because of the sound than for their longer durability and resistance to harmful external influences.

In general, the sound of metal pipes was considered to be more harmonic, radiant and carrying, while that of wooden pipes was considered to be more fundamental, dark and soft. But the influence of the material is usually overestimated, because a variety of elements contribute to the sound of the individual pipes, from the dimensioning of the pipe cut (height and width of the labial window, course of the labial edge and the core gap), individual pipe treatment, wind inflow, position within the instrument, etc. etc. Traditionally, certain registers of rather dark sound character such as subbass or bourdon as well as some flute registers such as flauto traverso were made of wood. In some organ building traditions, in addition to the usual 8' open diapason in the front, it was also customary to arrange another 8' wooden open diapason inside (for example, the "Portun" 8' register in Austria) as a sound variant.

But with metal pipes, however, there are certain differences - noticeable in the sound - between the selected raw materials. Generally, these are made of alloys of tin and lead in various percentages; in addition, there are other metals such as iron, copper, antimony, arsenic, bismuth or tungsten in sometimes barely measurable proportions. As a rule, these trace elements are impurities of the raw materials, especially tin ores, undesirable, but hardly removable completely during smelting. Only antimony was sometimes deliberately added to solidify pipes with a high proportion of lead in the metal.

Traditionally, continental organ builders measured the ratio of tin and lead in "Lot" of 16 parts. Sixteen-lot pure tin is only rarely used, and only for façade pipes in special cases, fourteen-lot pewter, one of the most common alloys with a high tin content, consists of 14 parts of tin and 2 parts of lead; the so called "probzinn"is an frequently used twelve-lot alloy (75% tin to 25% lead). Usually a certain low proportion of lead is desirable, as this facilitates the processing of the metal. When organ builders apparently speak of "metal" as a pipe material in a neutral way, this refers to an alloy with only slightly higher or approximately the same tin content compared to lead content (later also called "natural cast"). If the tin content is still lower, the organ builders called the material "lead";but pure lead pipes are rather rare, because the material gets too soft and larger pipes deform under their own weight - with all sorts of unpleasant accompanying phenomena. The sound differences between "tin" (16- to 12-lot), "metal" (about 11- to about 8-lot), and "lead" (tin content below 50%) are similar to those between metal and wooden pipes: the higher the tin content, the more harmonics, the lower, the more fundamental in the sound character. Therefore, ranks where strong harmonics were desired (for example, deeper principals or strings) were made of "tin", those with comparatively weaker harmonics (high principals, mixtures, chimney flute) made of "metal" and fundament ranks (wide flute parts) are made of "lead".

As a rule, in an organ there are both metal and wooden pipes. Some registers are manufactured "properly" only from certain materials, such as façade pipes made of "tin". However, over the centuries, organ builders have repeatedly tried to save on materials, sometimes under pressure from the clients, in order to keep the total costs down, but sometimes with less honorable motifs. Manuals for organ reviewers are very detailed in their descriptions of material samples - as for example the observation that an organ pipe of 15 % lead content does not yet but one of 21.5 % lead does already leave a delicate grey line on a piece of paper. (Walther Edmund Ehrenhofer, Taschenbuch des Orgelbaurevisors, Vienna 1908, p.172). Some decorative virtues arose from the necessity of not being able to afford the expensive tin, especially for the deepest pipes in the front. In some countries, for example in England or in Spain and Latin America, it became common to paint front pipes in colour. Other solutions were occasionally less successful: organs with tin-foiled wooden pipes in the façade, such as the organs in Basedow or in Maihingen, show that the optical lamination by tin foil did not last.

Organs, which only had pipes made of metal or only of wood, were always rare exceptions (except for small organs with only a few stops): The organ of the Silver Chapel in Innsbruck, which was made in Italy, or the organ of Frederiksborg Castle by Esaias Compenius, both originated in the early 1600s, both with wooden pipes only, were admired over the centuries, as well as the Great Ceremonial Organ of the Klosterneuburg Abbey near Vienna by Johann Freundt with metal pipes throughout. But the amazement of posterity was also due to the solution of problems that were apparently not manageable, achieving the sound of metal ranks with wooden pipes and vice versa. The efforts involved did not invite imitation, and so these instruments remained what they were always supposed to be: unique masterpieces.

© Greifenberger Institut für Musikinstrumentenkunde | info@greifenberger-institut.de