Capricci

The Baroque era loved visual puzzles, features not easily recognizable or being something else of what they appeared to be.The „Theatrum mundi“ was kept vital by the art of dramatics and hardly any other object of sacred architecture offered more options than a resonating organ which almost demanded to get sculptured in a way according its solemn sounds.

In hardly any other time organ cases were designed more fanciful than during the 17th and 18th centuries. Some areas cherished uniformity like centralized France, some other preferred individual or even phantastic variety like catholic southern German areas, where hardly any two organs are alike.

The creative game with the organ exterior could reach a stage of no longer recognizable as organ; designs existed without any visible organ pipes, although usually not considered convincing.

But usually the main focus of a fanciful and unique design was a general shape of the unexpected. What could be expected was a more or less rectangular case with high towering pipes divided in a sequence of fields and towers of uneven number. The first pattern of variation - unspectacular but very rare was to sort the pipes in an even number of fields and towers. (pic.1).

A particularly popular field of experiments formed choir organs of abbey churches – usually rather small instruments in comparison, but the common placements among choir stalls close to altar was a certain challenge, as this involved no obstruction to free view of the altar and sufficient space for the praying convent.One possible solution was constructing the organ with more or less horizontal pipes usually without a pipe front. (pic. 2 and 3)

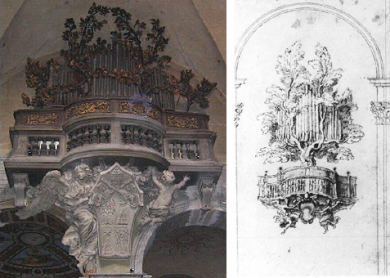

A different solution was the Austrian pattern of „ pulpit organ,“ in symmetry to the proper pulpit, in design and symbol very original pattern.

(pic. 4)

In some designs it was attempted to make the organ visually „vanish“ by encasing it into a wall orifice (pic.5/6), sometimes revealed by a shallow front. But even those caseless fronts are usually designed with great care, even if hardly visible from the nave.

A comparison in size of the choir organs of two of the most important monasteries in the wider alpine range shows the enormous in some ways opposing design options. The choir organ of the cistercian abbey Stams (pic.7) is rather a miracle of compactness: In the centre of the stalls and partially integrated it offers space for 12 ranks in a case of about six square meters on ground and hardly one an a half meters in height. In contrast the two choir organs of the benedictine abbey of Ottobeuren expand the limits placed atop the stalls. The two galleries bear symmetrical organs of a size exceeding some comparable main organs (pic.8).

In some regions it was common to memorialize benefactors or the ruling authorities in some way. The common pattern of a plain inscription sometimes was exceeded by turning the organ itself into a memorial. One of the most famous examples is the organ of Sa. Maria del Populo in Rome, designed in the circle of Gianlorenzo Bernini. Its „case“ is in oak shape citing the coat of arms of the benefactor Pope Alexander VII; the organ pipes appear like grown stem and branches (pic.9/10).

In Austria it was common to apply a double-headed eagle somewhere; hardly ever so prominent as with the former organ of Landeshut in Silesia, where its parapet organ was designed as one (pic.11).

All these examples illustrate the enormous phantasy and multitude of designs the age offered. They also reveal the organ was not only understood as an audible but also a visible work of art for the delight and pleasure of the audience.