Introduction

The mechanism of a harpsichord was simple. At the back end of the key was a jack, which contained a pivoting tongue with a plectrum embedded in it; this struck the string at a right angle and plucked it. The arrangement of the strings within the instrument itself, whether at a right angle, diagonal, or parallel to the keyboard, played a minor role; the plectrum simply needed to hit the string. This allowed harpsichords to be built in many different shapes. Even the oldest sources show both grand piano-shaped instruments as well as smaller models that could be placed on a table.

"Mechanik der Poesie – Besaitete Tasteninstrumente des 15.-19- Jahrhunderts"

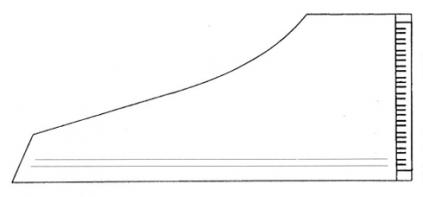

The most important type was the wing-shaped true harpsichord, which was also mostly called "Flügel" in Germany before this term was transferred to the hammer piano around 1800. Additionally, there was also an upright variant of it, the claviciterium.

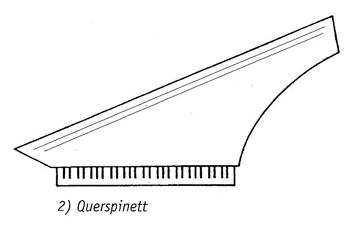

The naming of the smaller table models has varied by country over the centuries and can be somewhat confusing: Two terms, virginal and spinet, can be traced back quite early, but their assignment to different types of instruments varies greatly.

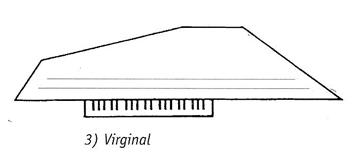

Modern practice distinguishes the two types based on the arrangement of the strings within the instrument: In the virginal, the strings run parallel to the keyboard, while in the spinet, they are arranged at an angle. However, according to this easy-to-identify distinction, some types that were called spinets at the time, such as the polygonal Italian spinets of the 16th century, are classified under virginals.

The outline shape of virginals is usually rectangular or hexagonal with a long front side, while that of spinets is more or less triangular with a long back side, often in a typical distorted wing shape, known as the oblique spinett, which was popular for a long time as a home music instrument in Italy, Germany, and England.

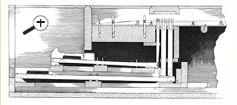

The small forms of virginal and spinet and the upright claviciterium usually had only one manual and typically only one register, meaning as many strings as keys. However, wing-shaped harpsichords often had multiple registers, and those from Flanders, France, Germany, and England frequently also had two manuals. This significantly enhanced the musical possibilities. However, the mechanics of these multi-manual instruments became more complex in the attempt to allow for different register combinations and thus differentiated volume and sound contrasts.

In individual European countries, different constructions were developed for this purpose, allowing to identify distinctly distinguishable national harpsichord building schools. This significantly contributed to the differences in sound and musical qualities. Thus, between the 16th and 18th centuries, a remarkable variety of harpsichord forms emerged, featuring an abundance of different details and nuances, despite the identical basic technology.