Reeds

Acoustics

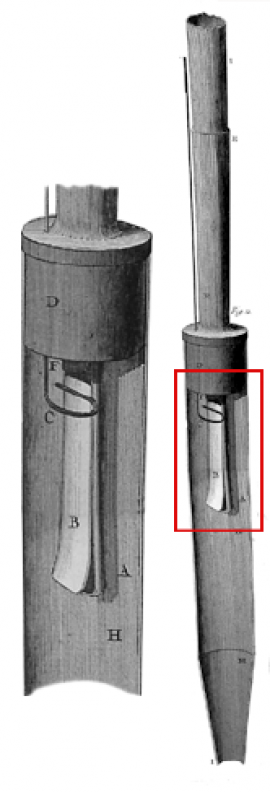

In these stops a flexible metal reed (usually of brass) produces the sound of the pipe by frequently interrupting a passing air stream between the reed itself and the shallot of the pipe head. The pitch thus produced corresponds to the proper pitch of the metal tongue itself. The split air stream transports and amplifies this sound and the coupled resonator above colors it by amplifying or damping different harmonics in the sound spectrum, depending on its length and shape. The reed produces both a striking fundamental and rich harmonics. In addition, there is a characteristic noise element, created by the flapping of the vibrating reed on the edges of the shallot (hence the term beating reed), which additionally amplifies and contributes substantially to the typical buzzing sound character.

The Resonators

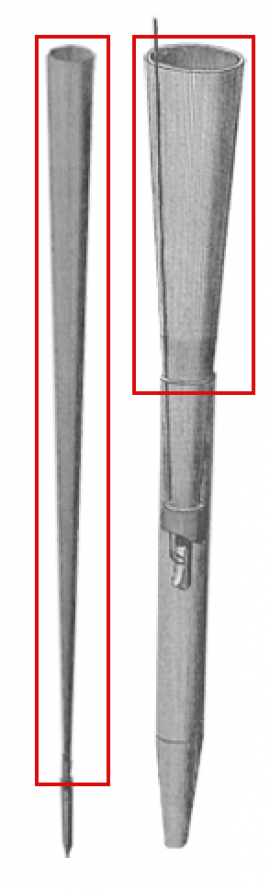

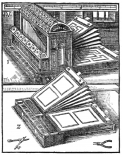

Most of what is visible of a reed pipe, the resonator, is not essential for actual sound production, and so it is quite possible to build reed pipes without resonators. Those pipes are, however, extremely rich in overtones, and the noise elements of the pipes are in no way subdued, so that their sound has something wild and occasionally uncultivated about it for some listeners. Reed stops without or with very small attachments are called "Regal". They enable an extremely space-saving construction of pipes for relatively low sound ranges. For this reason, they have traditionally played an important role in the construction of small organs, but also parts of organs in confined spaces (such as chest positives). A small organ, which has only one or more regal stops, is also called a regal. In the 17th century, the regal was valued highly as a useful far-carrying instrument, easy to transport due to its small size, until the typical sound character went out of fashion.

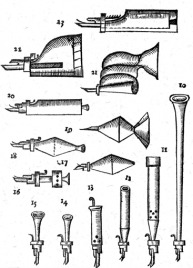

Therefore, reed stops are first distinguished by whether they have no or only relatively small resonators, or relatively large ones. A large resonator may look (and act) like a megaphone: the sound gets somewhat stronger, but at the same time - depending on the form and length - specifically shaded. The longer and narrower such a resonator the more the high partial frequencies of the tongue tongues are damped. However, there is hardly any limit to the design of such resonators. Over the centuries, organ makers developed a unique field of experimentation developed for the organ builders with a multitude of types of resonators, whether cylindrical, conical, in combinations thereof, in coils, with multiple tubes inserted and reciprocated, with openings in different places and in different shapes and sizes to dampen or enhance individual frequency ranges and shape the sound of reed stops. Reeds which were closed at their top ends, were also called "stopped" ranks, although the analogy to the stopped flutes leads astray: a completely closed reed pipe would not sound at all, so there must always be an opening somewhere to release the wind into the atmosphere.

Reed stops formed an excellent basis for imitating sounds of other instruments or the voice, because from the starting material of their rich harmonics a specific sound character could be filtered out more easily than adding a range of harmonics of an oboe or trumpet to a fundamental by means of adding multiple flute pipes (but this was also tried with some success ->"compound stops").

The different reed stops

Reed stops usually carry names that refer to the sound of what they imitate. In addition to wind instruments, these were the human voice, but also special animal sounds such as the "Bärpfeife", which could and should hum audibly like a bear. The sound of the string instruments was also occasionally taken as a model ("Geigend Regal" by Praetorius; "Viola da gamba" by Arp and Frans Caspar Schnitger). The baroque imagination and not least the humor of the organ builders could romp around here, and registers like the "Jungfrauenregal" 4' (Michael Praetorius: 'It is called / because it is ... like a virgin voice / who wants to sing a bass") testify to this - in later, more humorless times such voices were usually removed again.

The most important stops with long resonators assume dimensions comparable to those of flue stops. The lengths of the "Trombone" and "Clairon" stops are 2/3 to approximately half, the stop "bassoon/oboe" about 1/3 to 1/4 the length of a corresponding flue stop. A trombone 8' thus had a cup of six feet in length, a trumpet one of four feet, a bassoon of about three feet. What they all have in common is a conically extended resonator shape, if made of metal as is customary for the trumpet stops, and with an extension at the end, reminiscent of the bells of the model instrument. Some wind instruments with cylindrical bores were imitated very similarly too (Fig.) with corresponding resonators ("Krummhorn" in Germany or "Cromorne" in France, despite name correspondence of different scale and sound!)

Organ builders developed shorter and much more complex resonators for imitating the human voice. They mostly consisted of a combination of short cylindrical and conical or bicone sections; often there was also a marked narrowing at the upper end that filtered out certain higher harmonics.

The pursuit to create "Vox humana" stops to imitate the sound of the human voice by means of flue as well as reed pipes was a hardly feasible undertaking any way. Rather, the sound of such a stop should be rich in specific formants (vowel sounds) that change over the range of the register, giving the impression of singing without words. As an undulating stop (such as the Italian voce umana) or reed stop (as in Germany and France) in connection with the tremulant, these stops were nonetheless among the most highly valued solo stops of the organs in the 17th century. and 18th century.

However, building and using reed stops was controversial for another reason. Many organ builders were reluctant to offer reed stops in large numbers, and many, especially smaller instruments, do not have any reed stop at all. The reason was their reaction to change of temperature: Flue and reed stops react in a different way then, because labial stops decrease or increase in pitch depending on heating or cooling of the ambient temperature, whereas reeds remain largely stable. The change of the seasons therefore required the organist again and again to retune the pipes - in the theory of labials, since they went out of tune (but almost evenly in their entirety), but in reality the rather (few) reeds to keep the workload down. If, for example, a church did not have a permanently appointed organist, or did not find someone who was familiar with organ tuning, it was often wise to refrain from reed stops.

A contemporary anonymous author described this conflict in a description of the famous organ of the Inner Temple Church in London:

'It hath several excellent stops, as the Cremona stop, ye Trumpet stop, the Voice humane, which last stop is set to Mr. Gascell’s voice, who can reach one of the deepest basses in England. These three stops, tho’ pleasant to the ear, are of no duration, and must be tuned two or three times a month, which is chargeable, and cannot be performed by an organ maker; but commonly the organists beyond sea are better skill’d in the art of tuning their instruments, which few or none in England do understand.'

But for large organs in representative church rooms, reeds were considered indispensable. Italian or South German organs usually had only a few reed stops, but a proper French organ was incomplete without a trumpet 8' in every keyboard, a clairon 4' in the pedal and main organ and if possible a bombarde 16' (for the Grand Jeu) and at least one solo stop cromorne 8', voix humaine 8' or hautbois 8'. Similarly there is hardly any Spanish organ without trumpet. The sound effects made possible by the French reeds also impressed numerous organ builders in England ("Cremona" 8' misspelled from French "Cromorne") and Germany and appear in important organ buildings of the 18th century. by Riepp (Ottobeuren), J.A.Stein (Augsburg, Barfüßer) and the Silbermann family (Freiberg, Dresden).